Atajos

El nacimiento de la 'Riviera francesa'

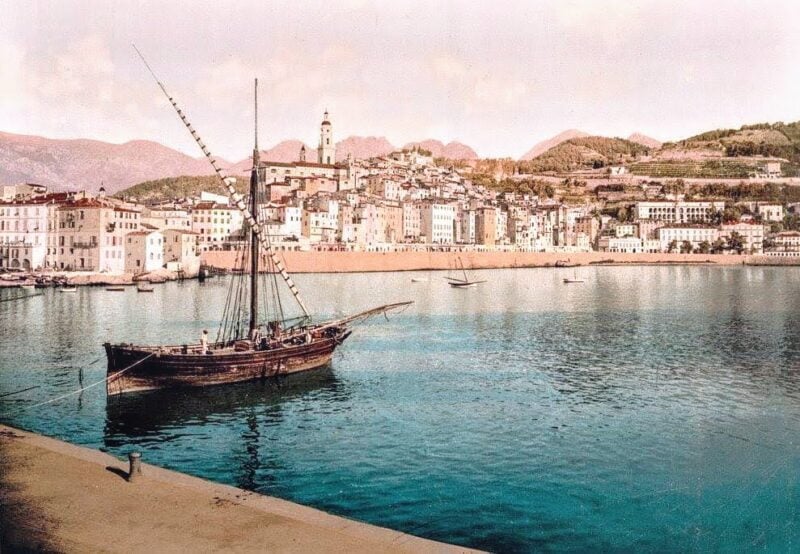

The highly-Instagrammable seaside town of mentón may well be lesser known than its Riviera neighbors, but it –along with Nice– was instrumental in establishing the French Riviera as possibly the oldest winter vacation spot in the world. Jean Cocteau painted his famous frescoes of love here, and English nobles planted exotic gardens around Italianate villas shaded by palm trees.

Tribes and Romans

Traces of occupation go back 3000 years or so, but until the end of the 18th century, the area later known as the Côte d’Azur was a remote and impoverished region, known mostly for fishing, olive groves, and flowers used in perfume. Tribal people now called “Ligurians” were the first known inhabitants of the French Riviera in historical times.

Not much is known of these aboriginals, only that they built fortified villages, notably on the site of modern Nice. Some centuries later, Greeks from overcrowded Phocaea moved, first into Massilia (Marsella), then outwards to Hyères and Nice, as they tended to do wherever there was a chance of industry or commerce.

The Greeks brought the vine (thoughtfully informing the earlier inhabitants what could be extracted from the wild stock indigenous to the area) as well as olives and other products of their advanced civilization. The Celts, who were at the same time putting down roots as far south as the Riviera, preferred the wilder hill country up from the coast — and to raid rather than trade.

The inhabitants of the land along this coastal strip had been accustomed to operating independently of “central” control. The Roman’s forced occupation –as commemorated by the trophy in La Turbie— was an important exception, but even then the numbers of occupiers was small and they had a specific task, to defend Roman access and trade routes, with little concern for the local inhabitants.

After the Roman retreat, and before the 18th century, the pockets of inhabited land were tiny compared with the wide swathes of rocky, scrubby hillsides and boggy river estuaries. Communities were isolated. Mosquitoes drove everyone mad, and getting around was dangerous and slow (little has changed).

Sobre todo, era un lugar aburrido, pobre e inculto, ruinoso y abandonado por el mundo exterior. Estaba esperando ser “rescatado”. Dividida entre esferas de influencia francesa e “italiana”, no era una sociedad coherente ni siquiera dentro de sus fronteras conflictivas. Luego vinieron los británicos para transformar la zona y crear la “Riviera Francesa” tal como la conocemos…

Cómo los británicos transformaron la Riviera francesa

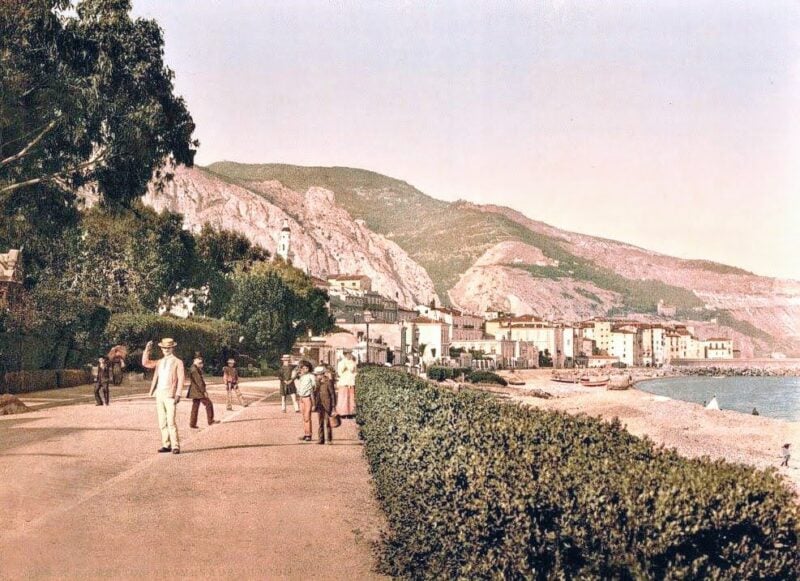

In the 18th century, a taste for travel developed amongst the English aristocracy, especially spending the winter on the French Riviera. Viewed as a Garden of Eden, the South of France was also the natural ‘route’ to Italy and its culture, which was a fashionable place to experience, among the elites.

This seasonal migration of the English upper classes was quickly copied by other European elites, all in search of a mild winter. At the beginning of the 19th century, the health argument emerged – people would go to these winter resorts as a medical treatment.

El siglo XVIII creó la estación invernal y el XIX la selló.

El primer viajero británico que describió los beneficios de la zona para la salud fue el novelista Tobias Smollett, who visited Nice in 1763 when it was still an Italian city within the Kingdom of Sardinia. He brought Nice and its warm winter climate to the attention of the British aristocracy with ‘Viaja por Francia e Italia (particularly Nice)‘, written in 1766. It’s a highly-amusing travel diary in the form of letters, in which he fell in love with Nice, foresaw the merits of Cannes (then a small village) as a health-resort, and envisioned the possibilities of the Carreteras de la cornisa. Poco después de su publicación, británicos enfermizos comenzaron a viajar a la Riviera francesa, convirtiéndola así en la primera zona invernal del mundo.

Casi de inmediato, el médico escocés Juan Brown Recogió esta idea y se hizo famoso por prescribir lo que llamó "climatoterapia": un cambio de clima para curar una variedad de enfermedades. En 1780 publicó su 'Elementos de la medicina', que durante un tiempo fue un texto influyente. Expuso sus teorías, a menudo llamadas el "sistema de medicina brunoniano", que esencialmente entendía todas las enfermedades como una cuestión de estimulación excesiva o insuficiente. El controvertido y simplista llamado 'Teoría brunonia’ dictated that all diseases fall into one of two categories: those caused by the absence of stimulus and those caused by too much stimulus. He and his contemporaries regarded the Mediterranean climate as offering a considerable variety of tonic and sedative environments.

Manteniendo el impulso, el médico británico John Bunnel Davis escribió su libro de 1807, 'The Ancient and Modern History of Nice'. Se convirtió en otra voz más que defendía el efecto curativo de la Riviera francesa sobre las enfermedades. El escribio, “¿Quién puede dudar por un momento de que es más probable que la salud regrese cuando el camino hacia su adquisición está sembrado de flores; ¿Cuando la carga dolorosa que abruma el alma es aliviada por ocupaciones agradables, y cuando la ansiedad se cambia por paciencia y resignación?”

This theory dominated European medical thought for roughly one century, until the late 1800’s, and the entire Mediterranean coast became something of a winter health resort for sufferers from all sorts of diseases (especially tuberculosis, which was killing one in six in England). Once Napoleon had been defeated in 1815 and peace prevailed on the continent, the British in particular began to flock to Nice, mostly for their health, and always in winter.

François-Joseph-Victor Broussais, un famoso médico francés, se hizo muy popular a principios de la década de 1820; su teoría medicinal se basó en la teoría brunonia. El historiador francés Paul Gonnet señaló que los médicos enviaron “a nuestras costas una colonia de mujeres inglesas pálidas y apáticas e hijos apáticos de la nobleza al borde de la muerte”.

La popularidad de la Riviera francesa se disparó aún más cuando el médico británico James Henry Bennet comenzó a promover el clima de Menton como una panacea para la salud. Bennet había estudiado medicina en París y, después de trabajar como médico durante 25 años, contrajo lo que él mismo diagnosticó como tuberculosis (this was before they knew the cause was bacteria). In 1859, he claimed that he went to Menton to “…die in a quiet corner, like a wounded denizen of the forest” (but it’s more likely that he was familiar with the Brunonian theory and went to be cured). But instead, his health greatly improved, and he visited Italy the next year, but found the “unhygienic state of the large towns of that classical land undid the good previously obtained”. Unimpressed with Italy, he returned to Menton and started a medical practice.

Cuando estuvo completamente curado, regresó a Inglaterra para informar a sus pacientes sobre Menton. Se corrió la voz rápidamente, ya que se incluyeron pacientes notables de Bennet Robert Louis Stevenson y Reina Victoria. From then on, he spent every winter in Menton.

Su libro de 1861 'Invierno y primavera a orillas del Mediterráneo' rápidamente impulsó la popularidad de Menton (entonces llamado 'Mentone') como destino. Bennet consideró que el clima cálido y seco de la Riviera francesa, así como una dieta adecuada, curaban a los enfermos de tuberculosis. Posteriormente se tradujo a otros idiomas y se publicó en otros países, lo que atrajo a todos, desde alemanes hasta estadounidenses, a Menton. Pronto otros médicos se unieron al coro.

While Lord Brougham había puesto recientemente Cannes en el mapa for carefully-selected members of London’s upper-crust society, readership of Bennet’s book was widespread and created an overwhelming influx of tourism. Many aristocrats, mostly with various health ailments, flocked to the French Riviera with the hope of getting cured. Without a doubt, more than one ‘consumption’ victim had asthma rather than tuberculosis, and getting away from the cold, damp and very smoggy British cities would have been all the ‘cure’ they needed.

En 1882, Reina Victoria took Bennet’s advice and came for an extended vacation, opening the floodgates for royals and high society to follow. She visited eight times after that and told her friends about how much she loved the area.

Por sugerencia de la Reina, Winston Churchil eligió pintar sus paisajes, y muchos escritores de viajes famosos del siglo XIX (como Robert Louis Stevenson, Somerset Maugham, Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, HG Wells, Edith Wharton, Louisa May Alcott y Aldous Huxley) comenzaron a escribir sobre ello.

Se construyeron ferrocarriles, las grandes villas reemplazaron a las granjas de piedra y los carruajes ornamentados que transportaban a duques y príncipes comenzaron a aparecer a lo largo de las carreteras de la costa alta sobre el mar resplandeciente. Poco después, la Riviera Francesa se hizo famosa en los EE. UU. como un lugar de vacaciones glamoroso y de alto nivel para celebridades y la jet-set.

A lo largo del siglo XX, los estadounidenses transformaron aún más la Riviera francesa, y muchos de los autores y estrellas de cine estadounidenses más famosos pasaron tiempo o se mudaron aquí. Superestrella Grace Kelly se casó con el Príncipe de Mónaco, Rita Hayworth conoció y se casó con un príncipe aquí, Sean Connery bought a villa in Nice y filmó escenas de 'Never Say Never' en el casco antiguo de Menton, y los estadounidenses con riqueza o fama pasaban sus vacaciones aquí.

Sin la influencia de los británicos y estadounidenses ricos, la Riviera francesa no sería lo que es hoy.

Los franceses finalmente descubrieron la zona como lugar de vacaciones mucho después que los angloparlantes y, finalmente, comenzaron a construir casas de vacaciones y bloques de apartamentos más pequeños a lo largo de la costa. Ahora, la Riviera francesa es una mezcla poblada de turistas, expatriados de habla inglesa y franceses.